Following 20 years of front line service in the Royal Navy I was appointed to be the Officer Commanding of the Warfare Training Group (OC WTG) in HMS COLLINGWOOD, the Navy’s largest training establishment, and the biggest in Western Europe.

Being responsible for all Warfare Training to the Fleet, I found myself on a journey that would embrace modern adult learning techniques, higher education (HE) practice and the development of some really strong links with Advance HE, especially through the Leading Transformation in Learning and Teaching (LTLT) course. My journey would culminate in achievement of Senior Fellowship of the HEA and a wider recognition of the value of higher education in the military.

A large part of my new job focused on the education of new Principle Warfare Officers (PWOs) who have been in the Navy for around 10 years already and were learning new skills in order to take charge of the Operations Room of a modern warship. This year long course, accredited by Kingston University and part of the Royal Navy’s in-service degree programme is a pivotal, almost career defining course that teaches weapons, tactics and procedures to all those Officers who ‘fight’ the ship at sea.

The Navy has invested significant money and effort into developing a synthetic training environment which allows my students every opportunity to ‘learn by doing’ and much of their assessment is done in the simulated space. However, underpinning all of this practical training is a significant body of academic knowledge which, on arrival, I found to be delivered in a wholly didactic manner with little or no appreciation of the students as individuals.

How could we be training people to fight a ship against supersonic missiles, yet still be using white boards and lists to deliver the declarative knowledge they needed to properly understand what they were being asked to do?

With significant support from my boss at the time, I attended LTLT13 (my thanks, as ever, to Doug Parkin who is an inspiration and was so welcoming to the Naval Officer who crashed the party and sat in the middle of a room full of academics) and looked to HE practices to develop new ways of delivering the PWO course. This would benefit the individuals themselves and, by extension, the Royal Navy at sea (why wouldn’t we want to train our people better?).

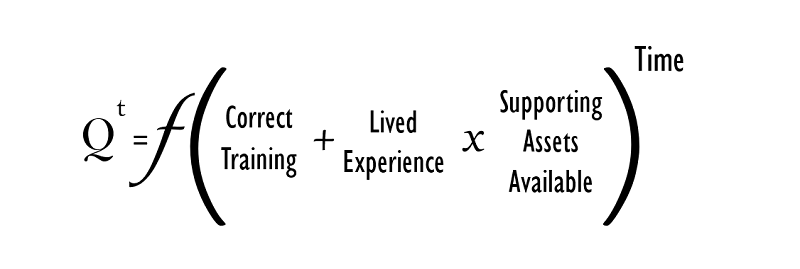

LTLT was an amazing forum that gave me the opportunity to develop and then discuss a functional expression of how I wanted to improve the quality of training (Qt) in the PWO course. I came up with this:

At its most fundamental, I saw quality of training (Qt) being represented as a function of:

-

the correct training (governed by a well-coordinated, constructively aligned and understood learning process and feedback loop to ensure we were delivering everything that was needed to satisfy the Key Learning Outcomes of the course), combined with;

-

the overall ‘lived experience’ of our trainees: how we teach them, the environment we create for them (including Diversity and Inclusion (D&I) but also the infrastructure around them) and how we made them feel by being in HMS COLLINGWOOD; and enhanced by;

-

the supporting assets we could make available to the training. This is the ‘bill’ that we as an organisation believed we could afford to achieve the right quality of training (the significant financial expenditure on simulation, for example is seen as a reasonable investment) – this includes physical equipment, the number of instructors, ships to conduct training at sea and so on. It is a force multiplier.

-

Finally, there is a correlation to the amount of time we could give to the training. That is not to say that the more time we train automatically results in a better output, but it is a carefully monitored (and expensive) commodity that will affect every aspect of Qt.

Looking at the PWO course, I considered which of those factors I would be able to influence. For the most part ‘supporting assets’ were a ‘fixed cost’ (personnel, availability of ships at sea to conduct some of our advanced training, the simulated environment for assessment and so on) and time was a factor that was so inextricably linked to cost I would be unlikely to be able to generate much more of it.

It became, therefore, about influencing the correct [type of] training and improving the lived experience of my students, in order to make the most of the fixed elements we had at our disposal.

In my vision for Quality in the WTG this meant focusing on the way we taught the course, ensuring the best balance between summative and formative assessments, encouraging deeper learning, treating the students more like adults and improving their enjoyment, involvement and understanding of how they learnt in order to better engage with the pedagogical innovations I wanted to champion.

And so I embarked on a series of interventions, guided by the discussions I had at LTLT that looked to offer more skills to my instructors, more empowerment to take risk in the classroom (better use of IT; innovations such as ‘flipping’ the classroom; significant use of group activities to share experiences and properly understand new information) and a coaching ethos that looked to use the significant number of assessments as another vehicle for learning.

Even in the disciplined military environment this seemed to work really well, and feedback from the students in the first year was incredibly positive (as were their results). My challenge remains to embed these changes into business as usual as new instructors come and go (our usual rotation of training officers is 12-18 months), and to shift the culture significantly enough that PWO students have a real desire to take charge of their own learning and development; but we have proven that HE has a place in Professional Military Education and I now have a whole clutch of Officers beginning their journey to Fellowship and Senior Fellowship of the HEA.

Advance HE runs Writing Retreats for those applying for Senior and Principal fellowship. These offer the rare opportunity of space and time to think via 1:1 peer coaching and expert analysis, in order to process your thoughts and craft your narrative for your Fellowship submission.

Leading Transformation in Learning and Teaching is one of our development programmes for those looking to develop their leadership skills. For more information on our development programmes, click here.

Ben Aldous is a Warfare Officer in the Royal Navy and was Commanding Officer of HMS IRON DUKE before taking up his role as Officer Commanding the Warfare Training Group in HMS COLLINGWOOD. He has responsibility for training nearly 500 Officers and Ratings every year in every speciality of Warfare.