The current HE landscape and resilience

Advance HE recently carried out a large-scale, rapid and generative project called Creating Socially Distanced Campuses and Education, involving 300 senior educational leaders from the UK and around the world. It was from this project that the idea of developing sustainable resilience emerged. The project produced six detailed reports, and in the Final Capstone Publication a specific section on wellbeing was included to bring together observations, ideas and approaches regarding health and resilience that came out of the discussions. The following extracts from a series of leadership interviews that were a key part of the Capstone Report provide a strong insight into the perceived risks and challenges:

- In the near term, I think there are risks from fatigue and anxiety as we continue to plan for an uncertain future,

- Many people need or want to ‘take a break’, reflect, rest and recharge,

- We need to be watching very carefully the stress on leaders and indeed on our staff and our students,

- Supported staff, in a kind and compassionate environment, will be more motivated and productive,

- Providing support for staff and student wellbeing creates a culture of care.

Whether focused on an individual, a team or the whole organisation this beautifully expressed notion of a ‘culture of care’ captures the essence of what will be needed to support wellbeing, engagement and a positive mindset based on belonging. No matter what the circumstances are that surround engagement, physically, spatially or virtually, it is through valuing relationship and appreciating the psychology of belonging that sustainable resilience will be built.

To set the scene for resilience further, an emphasis was also placed in the interviews on self-leadership, looking after yourself so that you have the resilience, compassion and capacity to look after others:

- The importance of leaders looking after their own well-being, in order to be able to look after others and their organisation,

- It’s a cliché, but looking after yourself is really important. Sleeping, eating, exercising and time off are essential to wise decision making.

The interesting paradox here is that sometimes to be selfless we have to begin by being selfish. We hear it every time we get on an aeroplane, ‘in case of emergency, put on your own mask first before assisting others’. A simple concept that makes intuitive sense – you cannot help others for very long if you don’t take care of yourself first. One of the follow-on blogs in this series will explore the journey from ‘being’ to ‘resilience’.

As regards leadership itself, and the role of the leader in relation to wellbeing and resilience, the following urgent observations illustrate how this is more important than ever:

- There are many stress-factors on wellbeing for staff and students, and the urgency of leadership acknowledging this, even as they experience it themselves, will be key,

- It is of crucial importance to have empathy and compassion and to demonstrate support for all,

- Talk to people to find out what is on their minds or troubling them,

- (What do you see as the most significant leadership challenges?) Leading a fatigued and weary staff through all these changes.

Resilience is not one thing and it is neither weakened nor strengthened in a single way. There are countless stories of individuals and teams triumphing in adversity, and likewise we can all think of individuals and groups who appear objectively to have significant advantages and close support and yet struggle to fulfil anything like their potential. Some of these differences may be very individual, others could be to do with social, cultural or structural inequalities, but without a lot of listening and a true insight into the world of the person concerned tailored support and understanding will be hard to achieve. It requires care-full listening, as the following interview extract powerfully highlights:

- Taking the time to try to imagine how things will be feeling for others whose experience can and will likely be very different from your own. Fear, loss, juggling home/home-schooling/caring responsibilities, isolation; all are happening to people and they have their work to do. For some this will be a happy escape. For others it may be the final straw.

Individual resilience

So, how are you feeling right now? How are you? How is your team? And how is your organisation?

There are enormous health and social implications associated with how people ‘feel’, not just in terms of whether or not they have an identified ailment or condition, but in relation to their mood and sense of self-worth and confidence. Positivity and a strong self-image lead to a multiplier effect, improving outcomes not just for the individual concerned but also through energising contact and communication for the colleagues and teams with which they interact – an important lesson in itself for leaders. On the other hand, the detrimental impact of feeling bad and negativity can become progressive, leading to a loss of wellbeing and a potential drain on the climate of the team.

‘How are you?’ is probably the biggest and most significant question we ever ask, but sadly it often attracts the smallest of answers – ‘fine’ or ‘okay, thanks’.

The American Psychological Association defines resilience as “the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress” (Building your Resilience, 2012). Notwithstanding individual difficulties and challenges, colleagues working in higher education have collectively experienced significant adversity and trauma over the last six months arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. The collective spirit that has been displayed in the sector response to facilitating campus closures, moving teaching online, designing alternative assessments and supporting individual student needs, has been nothing short of extraordinary, and has probably saved the day in terms of community wellbeing. However, overcoming the initial hurdles takes one kind of energy, the resilience needed to remain engaged with the continuing changes and uncertainties is quite another challenge. This takes sustainable resilience, which requires conscious attention and commitment to develop.

In discussing personal resilience, it can be useful to think about triggers and traits. Firstly, the things that can trigger our resilience to become challenged or diminished, and secondly the traits of more resilient people that we can all aspire to foster and go on developing. The triggers are broadly as outlined in the definition of resilience given above. Whether single triggers or combined, large events or small, in isolation or cumulative over time the triggers can all have an impact. Taking as an example the COVID-19 experience of a lecturer in higher education, some of the triggers typically encountered may include:

- The unfamiliar – a period of social lockdown involving working from home using unfamiliar technologies and systems,

- Volatility – rapid and unforecast changes, and not knowing what the demands of the next week or month will be,

- Stress – the general stress of the community experiencing COVID-19, which is significant, and then specific stress factors such as supporting distressed and worried students,

- Isolation – communicating with colleagues through virtual channels and not having the regular structured and unstructured interactions with a college community,

- High workload demands – moving teaching programmes online, developing alternative assessment methods, and striving to maintain research activities,

- Stretch – moving from ways of working in which high levels of confidence have been established, to new ways of working and teaching that are outside the normal comfort zone,

- Uncertainty – not knowing what the future may hold as regards role, function and location, and anticipating a challenged HE landscape in which there will be significant financial pressures,

- Absorption – listening to and having empathy for the issues and anxieties being experienced by multiple others, staff colleagues and students,

- Loss – the sense of grief which comes when things we have invested in are significantly changed or curtailed, such as not being able to support and celebrate the conclusion of a student cohort,

- Fear – a conscious and unconscious apprehension around health and wellbeing, whether plans being made for reopening campuses and hybrid teaching are appropriate and responsible, and what happens if things get worse. The other fear is the one currently experienced by millions of souls around the world regarding the threat of contracting COVID-19 and the health of friends, family and loved ones.

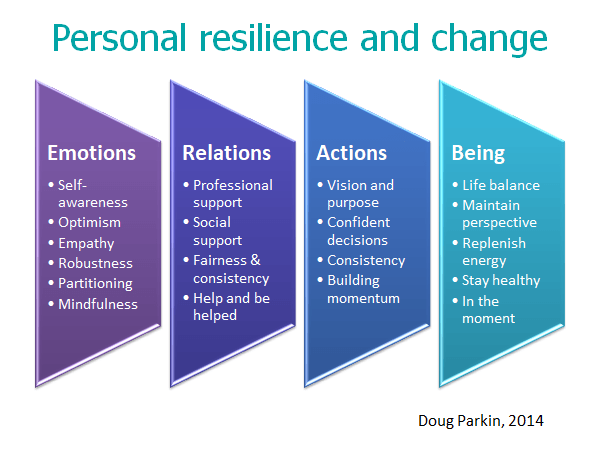

The traits of more resilient people have been researched and captured in various frameworks and models. Things like cultivating self-awareness, bouncebackability, fostering supportive networks, practicing acceptance, maintaining perspective, self-care techniques such as mindfulness, having a healthy balance between work and life, depersonalising events and positive framing are the kinds of traits that are associated with higher levels of personal resilience. And very importantly, many of these can be learnt, enhanced and developed. The well-known model developed by Professors Ivan Robertson and Cary Cooper puts forward confidence, purposefulness, adaptability and social support as the four key components of resilience. A free i-resilience questionnaire and report can be completed based on this linked to the Good Day at Work initiative. A model used by Advance HE (and previously the Leadership Foundation for Higher Education) on some development programmes in relation to personal resilience and change encourages reflection around four dimensions – emotions, relations, actions and being – as shown below:

A bridge between individual and team/organisational resilience is the important fact that inclusion builds resilience. It follows, therefore, that exclusion, marginalisation, inequality and unfair treatment are damaging to resilience and corrosive. The quest for greater levels of social mobility as regards higher education, for example, illustrates powerfully the structural disadvantages that exists in society and the pervasive inequalities that make the challenge of resilience so much greater where there are low levels of inclusion. COVID-19 has in many ways exacerbated existing inequalities (health, social, economic and educational), and experiences of isolation and disconnection may be far more challenging in terms of resilience for some people than others, linked to their backgrounds, needs, characteristics and circumstances. One of the follow-on blogs in this series will explore specifically inclusion and resilience.

Team resilience

There is a thread that runs through from individual resilience to team and organisational resilience, and the flow of influence runs in both directions. Resilient individuals feed up into a resilient organisation, and flowing the other way a resilient organisation is in a better position to foster and support resilient teams and individuals. The interdependence is virtuous. Similarly, a fragile organisation, one lacking in direction, conviction and means, will be a challenging environment for the sustainable resilience of many individuals.

Team resilience has been described as “a team’s capacity for positive adaptation which refers to a team’s collective potential to innovate and change to meet the demands of a difficult or novel situation” (Soon and Prabhakaran, 2017).

Relying upon the status quo, iterative change largely driven by internal factors, and cycles of activity that are broadly predictable, is the arena for middling levels of team performance in largely stable environments. How typical this is of teams will vary between organisations, but most large-scale enterprises will have this at least in pockets. Contrast this with what has been termed the soul of a start-up company (Ranjay Gulati, 2019), where something almost intangible “inspires people to contribute their talent, money, and enthusiasm and fosters a sense of deep connection and mutual purpose”. In searching for the essence of organisational spirit or ‘soul’, Gulati identifies three dimensions that combine to create a unique and inspiring context for work: business intent, customer connection, and employee experience. He goes on to observe that “as a business matures, it’s hard to keep its original spirit alive”, and that is equally true of teams as they become established within organisations. So, the kind of resilience that made a new team or enterprise innovative, exciting and risk-taking, will be different to the resilience of an established team with settled norms. Linking back to individuals, based on a combination of personality, background and experience, different people will thrive and discover their resilience in these environments in contrasting ways, and leaders need to be attuned to this diversity.

Coming back to the work of Soon and Prabhakaran (2017) exploring team resilience, they identify four qualities of resilient teams:

- Team learning orientation – Resilient teams are able to reframe challenges into learning opportunities and extract positive takeaways from negative experiences,

- Positive relationships within a team – Positive relationships lead to an environment of trust and safety which augments the team’s capacity for resilience,

- Clear sense of purpose – Resilient teams have positive aspirations and are able to envisage a positive future which energises and motivates perseverance,

- Diversity within a team – Resilient teams acknowledge the “value” each member brings and considers these differences as a strength to be leveraged.

As a model this provides a powerful insight into how sustainable resilience can be developed at a team level. And as with individuals, if these qualities were in place prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, all concerned will be in a stronger position to ride the turbulence, overcome obstacles, and continue to innovate, all with a spirit of collective commitment and engagement. For team leaders, these four qualities can be directly translated into four key intentions and actions:

- Reframe difficult challenges as learning opportunities and focus on the future,

- Invest in relationships and look to build trust and cohesion,

- Link everything to purpose and look to develop a positive team identity around this,

- Highlight the complementary skills and enhancing qualities brought to the team by different individuals based on their background, knowledge, experience and cultural perspective.

To take further the discussion of resilient teams one of the follow-on blogs in this series will explore the art of the resilient teaching team.

Organisational resilience

Some of this has been touched on in the previous section, contrasting start-up teams/enterprises with established ones, but understanding what makes an organisation resilient is hugely dependent on context. During times of growth, stability and reasonably settled market forces, organisational resilience may be quite a ponderous notion, revolving around things like having in place a five-year plan with an agreed vision and business goals that in many ways extend and continue a lot that has gone before. Financial soundness, steady, predictable demand, established client/customer relationships, a favourable competitive landscape, and a secure policy environment might all be features of such stability. Everything is relative, of course, as regards context, and in different regions of the world the concept of stability could vary considerably, and similarly what we considered volatile at the time may appear enviably stable with hindsight ten years later.

Organisational resilience has been described as “the ability of an organization to anticipate, prepare for, respond and adapt to incremental change and sudden disruptions in order to survive and prosper” (British Standards Institute, 2019).

There are numerous frameworks for considering organisational resilience, some linked to risk and governance and other focussed on various aspects of organisational development and strategy. Technical aspects may include things like business continuity planning and risk registers, whilst other approaches take in things to do with culture and the degree to which the organisational environment is responsive, innovative, creative and capable of moving with the times. Remaining competitive may be a concern for some organisations, remaining current and relevant may be the goal of others.

A very appealing developmental framework focused on organisational resilience is the Resilience Spiral developed by Dr Sven Hansen and The Resilience Institute. This brings together individual and organisational resilience in a powerful way and charts the connections between the two. At lower levels of the spiral agitated, unfocussed operations and lost productivity on the organisational side is matched with a state of overload, agitation, worry and mindless busyness in individuals. Higher up optimism, focus and effective decision making in individuals sits close to engaged, resonant leadership and culture. The parallels across the two sides of the spiral are clear and convincing, and as the text introducing the spiral says, “resilient people are the foundation for a successful and agile organisation or community”.

Disrupted times test resilience at every level. It was not so many years ago that the idea of disruptive innovation gained popularity (Bower and Christensen, 1995) and in relation to higher education some thought that as a result of rapid technological advancements an avalanche of change (2013) was coming that would change HE forever, such as the MOOCs revolution (massive open online courses). Looking back we can see that despite most HE institutions not having engaged in the kind of “deep, radical and urgent transformation” the An Avalanche is Coming (2013) paper envisaged “the solid classical buildings of great universities” remain standing and confidently in place. The threatening storms of change blew through and had an impact in other less dramatic ways, and change as is often the case merged with continuity to shape progress and development. However, could the COVID-19 pandemic now be the catalyst that combined with extraordinary developments in digital technology moves both ‘what we do’ and ‘how we do it’ in radical new directions? And how will this new avalanche of change test the resilience of higher education institutions, large and small, as they move to respond and adapt to a sequence of local and global disruptions on a scale nobody saw coming?

The final blog in this series will explore resilient organisations and higher education.

Resilience is not all or nothing. It comes in amounts. You can be a little resilient, a lot resilient; resilient in some situations but not others. And no matter how resilient you are today, you can become more resilient tomorrow. (Karen Reivich, 2008)

Doug Parkin, 20 August 2020.

Developing Sustainable Resilience in Higher Education – Advance HE, September 2020 Member Benefits theme

The suite of benefits for this theme will consist of:

- A blog series focused on developing sustainable resilience, beginning with this introductory piece and then four shorter follow-on blogs leading up to the webinar below:

- Inclusion and resilience,

- From ‘being’ to ‘resilience’,

- The art of the resilient teaching team,

- Resilient organisations and higher education.

- Webinar – Thursday, 24th September 2020, from 08.30 to 10.00 BST.

This webinar explored and discussed developing sustainable resilience with a guest speaker taking each of the three levels (individual, team and organisation) to share experiences, approaches and reflections, particularly related to surviving and thriving in the current pandemic age. Find out more.

Forthcoming Advance HE events and initiatives related to this theme:

- Student Retention and Success Symposium: Examining the role of mental wellbeing in the curriculum and university (16th September 2020),

- Nailing jelly to a wall: Providing wellbeing support in a time of uncertainty - Episode 1 (29th September 2020),

- Nailing jelly to a wall: Providing wellbeing support in a time of uncertainty - Episode 2 (24th November 2020),

- Mental Wellbeing in HE Symposium (17 February 2021).