Ask someone ‘how are you feeling right now?’ and the question is likely to be met with a deep breath, a pause for reflection, and a palpable searching for the right words. Emotional uncertainty is very much to be expected, at the moment, in both individuals and teams (when they connect for discussion). Answers, when they come, could be very wide-ranging:

- Pretty dreadful, to be honest

- Stunned, shocked, everything seems to be changing so fast

- I’m still trying to take it all in

- I’m not sure how I’m feeling…

- Better than expected

- At least the sun is shining (if it is – or another upside observation)

The role of leaders in providing emotional support, or allowing the space for honest emotional processing has never been more important. And doing this when the leader’s own emotional needs are in flux is doubly difficult. However, if we begin from the premise that the fundamental basis for leadership is relationship, then this true reaching out to others is more of a duty than a choice.

Crisis

Few, if any, in this new and rapidly evolving COVID-19 world would disagree that we are facing a crisis. Whilst this is not a piece specifically on crisis leadership, it would be useful to give that some definition.

When asked by a young journalist what his biggest fear was in leading the country former British prime minister, Harold MacMillan, is reported to have said “events, dear boy, events”. So, firstly, a crisis is definitely a significant adverse event. Ulmer et al. (2007[i]) go further describing a crisis as a “specific, unexpected, and non-routine event or series of events that create high levels of uncertainty and threaten or are perceived to threaten an organisation’s high-priority goals”.

Secondly, then, the two-fold emotional challenge of uncertainty and threat is another feature impacting all parts of the community concerned. The third factor to highlight is disruption. Everything from day-to-day routines and work habits through to fundamental questions of purpose and identity may be disrupted and come into question.

How, then should leaders respond? Well, as ever leadership is about balance. On the one hand, there is the pressure to act, to manage the situation, to focus on the task, get things done and make things right. There is something very natural here in organisational terms, as critically urgent situations readily trigger prescribed management solutions. However, the danger is that whilst a crisis may create urgency it seldom renders a predictable or stable landscape. On the other hand, there is the need to support people through the often difficult transitions that are confronted during un-forecast and unpredictable change. This is one of the great leadership balances, task-focus and people-focus, and having too much of one without the other is at best problematic.

Writing on the subject of crisis leadership, Tim Johnson (2017[ii]) observes that “crisis leaders routinely battle with two biases”. The first he terms ‘intervention bias’ and the second is about abdication. The intervention bias is the drive to do something or to fix things, perhaps before fully assessing the situation – or letting the proverbial dust settle – and this can lead to poor decisions and making inappropriate undertakings and commitments, and also possibly excluding the key people that need to be involved.

Abdication, by contrast, is about not taking responsibility, inaction, unhelpful delay which increases uncertainty and possibly even blaming others. Resolving these two biases is not simple, but the essence of it may lie in doing what really needs to be done in the here and now and then engaging in a process of “constant reassessment” working with others as the situation continues to unfold. In relation to incident-driven crises Johnson goes so far as to suggest that leaders should “resist the urge to do anything immediately”.

Emotional Intelligence

One of the key reflections for any leader can be expressed in the question “what do others need from me?” Sometimes this is about action, but at times of high emotional need this is often about listening and communication. The following is the text of an email sent by Marjorie Scardino, CEO of Pearson PLC, to all 28,000 of its employees in 2001:

Dear Everyone,

I want to make sure you know that our priority is that you are safe and sound in body and mind. Be guided by what you and your families need right now. There is no meeting you have to go to and no plane you have to get on if you don’t feel comfortable doing it. For now, look to yourselves and your families, and to Pearson to help you any way we can.

Marjorie.

To be more specific about the date, this email was sent on 12th September 2001, the day after the terrorist attacks in New York City and Washington DC. Pearson had offices on the 17th floor of the north tower of the World Trade Centre. Many other CEOs were sending communications about the possible consequences in terms of lost or diminished business revenues, but Marjorie (and she was known simply as ‘Marjorie’ throughout the company) knew that the Pearson ‘family’ needed a different kind of support. At that time Marjorie Scardino was the only female CEO of a FTSE 100 company.

Marjorie Scardino’s short but powerful email is sometimes used as an example of emotionally intelligent leadership demonstrated at an executive level. The seniority of the person sending this piece of communication, a chief executive officer, is fascinating in itself, but the principles of emotional intelligence are clear to see and would apply at any level.

Foremost is the principle of putting the emotional needs of others first. This on its own creates a cascade as behaviour often breeds behaviour and other managers and colleagues are likely to project the same kind of reassurance to each other and in turn outwards and onwards to clients and customers. Other features linked to emotional intelligence include the self-management of the author of the email, redirecting her own disruptive emotions for the benefit of the collective and being attuned to the moment, empathy, compassion, and the emphasis on relationship and showing genuine concern. There is a great deal to be learnt from this that is very relevant to today.

Emotional intelligence is a term that is widely used, sometimes very generally and in other contexts with a lot of specificity. The following two extracts from Peter Salovey and John Mayer (1990[i]) together provide a very useful and quite robust definition:

“The ability to monitor one’s own and other’s feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and action.”

“The ability to perceive and express emotion, assimilate emotion in thought, understand and reason with emotion and regulate emotion in the self and others.”

Key to the model of emotional intelligence, certainly as it has been popularised, is the notion of empathy or social awareness. This is not a new or modern concept, despite the wealth of more recent literature around emotional intelligence and positive psychology. Adam Smith (1813 to 1893), a philosopher of the Scottish Enlightenment, wrote about the capacity to think about another person and:

“…place ourselves in their situation… and become in some measure the same person with them, and thence form some idea of their sensations, and even feel something which, though weaker in degree, is not altogether unlike them.”

This is exactly the challenge for leaders supporting team members and other colleagues during these difficult COVID-19 times. And if there is one skill that reverberates with this it is powerful listening.

Threat and reassurance

The human response to threat is a much-studied area, including behavioural psychology, anthropology and more recently neuroscience.

Some discourses focus on the relationship between the ancient (primitive, primordial or reptilian) brain, which includes the amygdala and the limbic system, powerful emotion centres, and upper brain structures, particularly the prefrontal cortex which brings reason to bear on experiences based on our rational understanding of the world. The interaction between the two helps make humans emotionally sophisticated creatures: primitive and powerful emotional responses are usually mediated through reason and we learn from our experiences.

However, strong, enduring – and possibly existential – threats may cause underlying emotions to persist and go on affecting our behaviour and our choices even though we may not always be consciously aware of them. An example of this is the current emotional relationship between many younger people and the climate emergency. The emotions may go on arising and finding an outlet in people’s behaviours in an unpredictable way over an extended period of time, long after the onset of the crisis. Leadership support, therefore, needs to be in it for the long haul.

The literature on change, particularly as it relates to organisations, emphasises the often threatening nature of change, especially large-scale disruptive change with high levels of uncertainty. Ensuring a high level of collaborative engagement in the change process, if possible, can mitigate against this by giving people a voice, building ownership and fostering greater levels of collective commitment.

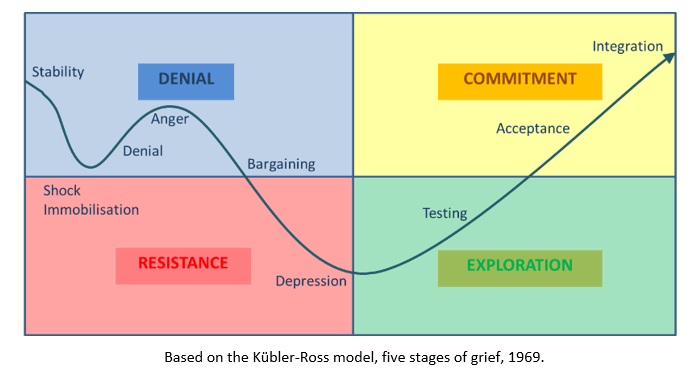

Broadly speaking, models of change fall into two camps, rational models and emotional models. A key feature of the emotional models is the research that has been done to identify and express the emotional response patterns triggered by change, in a reasonably predictable way, or the ‘change journey’ as it is sometimes termed. Most notable amongst these is the change curve (grief cycle) developed by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1969[ii]), that highlights shock/immobilisation, denial and anger/frustration as being the initial emotional sequence experienced by individuals. Shock can result, it should be noted, even if the circumstances leading to the change were perfectly visible to the people affected.

William Bridges (1991[i]), another author on change, tells us rather dramatically that:

“It isn’t the changes that do you in, it’s the transitions.”

Effective leadership during change is fundamentally about facilitating and supporting the transitions. Knowing that individuals may exhibit uncharacteristic behaviours, and express unexpected needs is a key part of this. Likewise, harmonious and high-performing teams may start to become stormy and feud in ways that require high levels of additional support. All of this is very typical of the emotional and social processes involved in adjusting to and assimilating complex change, such as suddenly changing to work from a new location and with a variety of quite possibly unfamiliar technologies.

To put it simply, a little bit of ‘crazy time’ can be expected. This may need to be addressed, in various ways, but above all else it is important that leaders go on being kind.

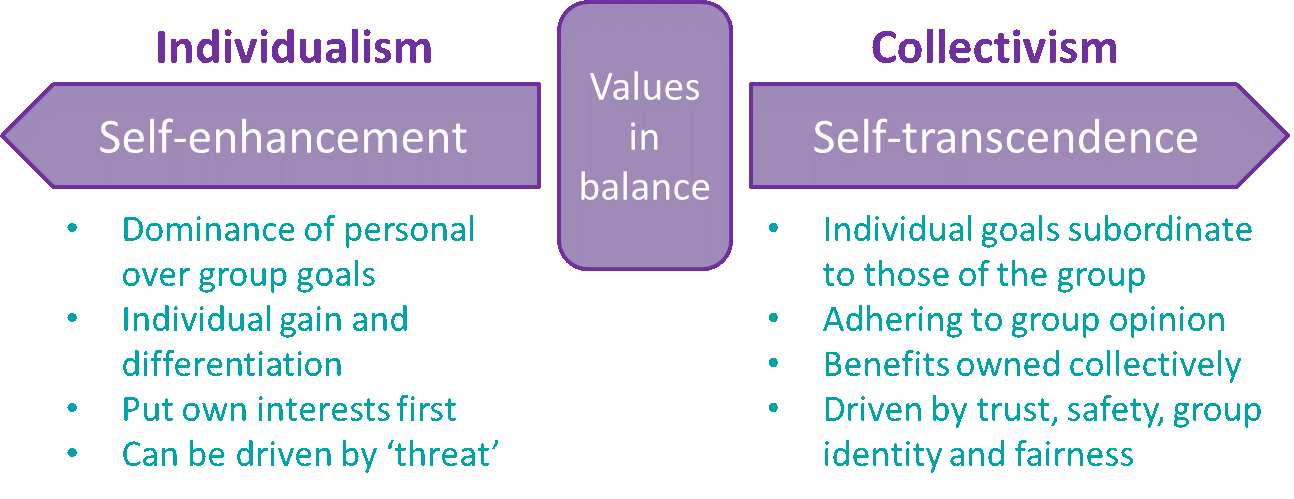

The perception of threat can also interact with human values, those deep roots that sit beneath and drive behaviour. Values are never singular or separate, they exist in a dynamic relationship with each other.

For example, individualism and collectivism are two value sets that can be held in balance, although many of us are disposed on one side or the other (Schwartz, 2006[ii]). When threatened, however, self-enhancement values (individualism) may take over and people can be driven to put their own interests first. Panic buying, as has been seen recently in the supermarkets and on the media, is a clear manifestation of this. Intriguingly, the very same people can be signing-up to volunteer and contributing to food banks, acts of self-transcendence (collectivism), just a few days later. This vacillating between values, looking after oneself and then being generous to others, is another feature of the emotional turbulence caused by crisis and disruptive change.

Providing reassurance, as a leader, is not an instrumental thing. You cannot prescribe to someone else a better way of feeling simply through the words that you say. Ultimately people discover and develop new emotional perspectives for themselves. This links to the journey along the change curve mentioned above.

A more accurate way of constructing the notion of reassurance is being available, caring and listening in a way that helps the other person explore and develop a deeper understanding of how they feel and why. Alongside this, kindness. This approach might be termed ‘authentic reassurance’ where the essence of it is a listening environment combined with time, space and support. The focus for the leader is on the conditions around the conversation rather than looking to direct or guide the conversation. Listen, in this context, can be expanded to include the following prompts:

L – listen with a whole-heart (rather than, perhaps, half-heartedly)

I – involve yourself by showing genuine concern and interest, and be kind

S – space for processing and reflection is the main objective

T – time is needed – remain available, this probably won’t be a single conversation

E – show empathy for the life and the world of the individual (or team) concerned

N – neutralise your own feelings and try not to project them onto the other person (people)

One definition of leadership suggests that it should be primarily focussed on fostering the best possible environment in which others can flourish and succeed (an important aspect of academic leadership). This is absolutely carried through into this notion of authentic reassurance.

Small acts of leadership kindness

Kindness has been mentioned several times throughout this piece. At the moment small (and less small) acts of kindness at a community level are finding recognition in newspaper headlines and on the airways. Kindness matters. In his foreword to the book Kindness in Leadership (2018[i]), entitled ‘Intelligence Helps; Kindness Helps More’, Colin Mayer powerfully observes that:

“The appreciation of kindness as not just a virtue but also a value and the significance of leadership in converting kindness as an individual virtue into a corporate value is the reason why kindness in leadership is so significant.”

To conclude, then, the following are some ideas for small acts of leadership kindness suggested by a range of colleagues in leadership roles at Advance HE, reflecting on the current dark and difficult times:

-

Be there for them.

-

Aim to do the right things for the right reasons.

-

Ask ‘in what ways could this be an opportunity?’

-

Challenges can also be opportunities (almost compelling innovation).

-

A bit of disclosure about your own experience helps to make a conversation more engaging and authentic (but not too much).

-

Ensure the work-day ends – a danger of working from home is that you are always on.

-

Encourage those we work with to follow up on their instincts to reach out to other colleagues. Create a virtuous and expanding circle of leadership kindness.

-

Speak to individuals, ask them how they are, how their families are and give them the chance to share their concerns if they want to, their personal worries and anxieties.

Just show you care about more than work progress. -

Recognise small achievements and always say thanks.

-

Arrange quick daily check-ins with the team, allowing them to be updated, see you and each other and make sure you show clear direction and recognition of the challenges.

-

Encourage people to exercise and maybe try out approaches such as mindfulness techniques.

-

Allow people, if possible, to flex their working hours to accommodate caring responsibilities.

-

Encourage people to structure their day for variety and to maintain motivation.

-

Be patient and supportive as people try out new technologies – maybe model a playful approach in which errors are learning.

-

Make sure that people have contact with other team members every day.

-

Admit that you do not have all the answers, but go on listening.

-

Prepare for emotional conversations. Think through how you might approach them authentically and become familiar with the support that is available in your institution.

-

Maintain both a sense of purpose (what we are here for) and accomplishment. Discuss achievements positively, especially at a team level, and aim to make them visible.

-

Keep the focus on learning – we never stop learning.

-

Show leadership kindness upwards, too. A crisis can make leadership a lonely experience. Those leaders/’your boss’ need support and encouragement, too.

We would also be very interested to hear about your small acts of leadership kindness. Advance HE will be creating an opportunity on Twitter for you to share them.

And on this theme of kindness, let us give the final word to the author Henry James (1843 to 1916):

“Three things in human life are important. The first is to be kind. The second is to be kind. And the third is to be kind.”

i Ulmer, R. R., Sellnow, T. L. and Seeger, M. W. (2007), Effective Crisis Communication: Moving from Crisis to Opportunity, 2nd edn. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

ii Johnson, T. (2017) Crisis Leadership: How to lead in times of crisis, threat and uncertainty. London: Bloomsbury Business.

iii Salovey, P. and Mayer, J. D. (1990) Emotional Intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9(3): 185– 211.

iv Kübler-Ross, E. (1969) On Death and Dying. London: Routledge.

v Bridges, W. (1991) Managing Transitions: Making the Most of Change. USA: Da Capo Pres Inc.

vi Schwartz, S. (2006) Basic Human Values: an overview. Available at www.yourmorals.org

vii Haskins, G., Thomas, M. and Johri, L. (2018) Kindness in Leadership. Oxon and New York: Routledge.