Participation and attainment gaps in UK higher education (HE) according to a person’s gender and ethnicity, rightly, get a huge amount of policy and media attention. But you would be forgiven for overlooking religion and belief. As the relevant data have historically been less systematically collected and recorded in HE, differences in participation and experiences by students’ religion and belief are rarely at the forefront of discussions about equality and diversity.

The benefits of new reporting requirements introduced by the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) for the academic year 2017-18, which made the return of data on students’ religion and belief mandatory, are now coming into effect. Using this data, the Advance HE’s research team has undertaken work to better understand how students’ journey through HE differ by their religion and belief.

Religion and belief of students in UK HE

One of the main barriers to understanding religion and belief, and one not limited to students and HE, is how we ask people how they identify their religion or what they believe. Do you belong to a religion if you were brought up following a set of behaviours and norms, but you do not regularly practice religious observances? On that note, where does regular practice begin? And what if you have doubted, or are doubting, some of your religion's teachings?

The answers to these questions are far from clear, and unsurprisingly people answer with very different responses depending on the wording of the question, the setting, or the preceding questions. Estimates of the proportions of people belonging to any religious group vary widely across all the most respected surveys.

In the context of the HESA data returns about religion, students’ self-identification is the focus rather than frequency of observances or specific beliefs. Our research revealed that around half of students reported belonging to a religion or belief (50.2%). The majority of these students were Christian (65.5%), followed by Muslim students (17.8%). Just under half of students reported no religion or belief (49.8%).

In comparison with estimates for the rest of the population, UK HE students were consistently more likely to say they were not religious or were Muslim, and less likely to say they were Christian. Perhaps most importantly, there were mismatches between how students and staff identified their religion. Higher proportions of staff said they were Christian, and lower proportions said they were Muslim, compared to students. It is possible that a misalignment of the beliefs of students and staff could lead to misunderstandings and miscommunications, and strengthens the case recently made by researchers at Theos for staff to receive religious literacy training.

Are there attainment gaps by students’ religion and belief?

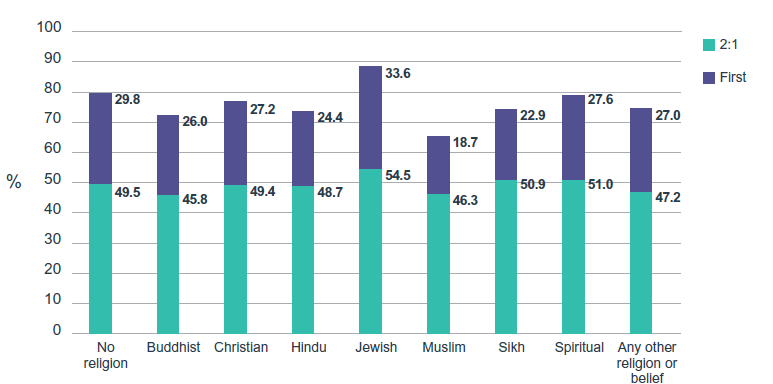

Advance HE’s research found substantial differences in degree attainment by students’ religion and belief. Most striking was the relative under-attainment of Muslim students. Overall 76.3% of students received a first or 2:1 degree, yet only 64.9% of Muslim students received a first or 2:1. This represents a 14.3 percentage point attainment gap between Muslim students and those with no religion or belief, larger than the BAME attainment gap of 13.2 percentage points.

Proportions of students who graduated with a First or 2:1 degree by religion and belief. Source: HESA data 2017/18, Advance HE analysis.

Recent qualitative research can give us insights into why this may be the case. Jacqueline Stevenson conducted interviews with Muslim students across the UK in 2018. Her report identified peer and staff perceptions (including outright Islamophobia), and a lack of acknowledgement of students’ religion, as factors that contributed to negative academic experiences of Muslim students. Furthermore, many institutions do not make practical adjustments to support religious observances for Muslim students.

This suggests that at institutions where there is a higher proportion of Muslim staff and students, their experiences may be improved. While unlikely to solve all barriers Muslim students face, peer support and understanding could help students both feel more at home at their university, and lobby the institution for any required changes. By linking information about students’ religion and belief, their degree attainment, and their institution's characteristics, our research showed that in institutions with a higher proportion of Muslim students or staff, the attainment gap was indeed reduced.

What’s next?

Advance HE’s report has highlighted the different experiences of students according to their religion and belief. These findings, combined with qualitative research, can help institutions to understand why there are participation and attainment gaps. However, there is clearly more work to do to address inequality.

Importantly, universities need to understand their own students’ religious makeup and their particular experiences and requirements. Our research has shown that not all universities have an attainment gap, but at some the gap is substantial. What can these latter universities do to improve the experiences of students from minority religious groups, and how can they enable all students to reach their potential?

It is much reported the religiosity is decreasing across Britain. There is no reason to expect this to be any different for students. For many students, attending university is their first step into independent living. It is a life stage where people start to question their assumed thinking, meet a range of new people and are exposed to new ideas. This is a time when many young people re-evaluate their religious beliefs, and either solidify their religious beliefs, change religion, or cease to hold any religious beliefs at all.

HESA encourages higher education institutions to update returns annually, but it is yet to be seen whether the data will provide an accurate insight into changing religious beliefs of students. At the very least, with the most recent data release for the academic year 2018/19, it will finally be possible to compare students from one cohort with the next to see how the religious beliefs of the next generation of graduates are changing.

Dr Natasha Codiroli Mcmaster is a researcher at Advance HE and author of Religion and Belief in UK Higher Education.

Download Religion and Belief in UK Higher Education

Advance HE published guidance in 2018 on how to support the inclusion of staff and students of different faiths and beliefs. This includes practical issues like timetabling, catering, recruitment and inclusive teaching and learning. Download the guidance