Professor Chris Warhurst is Director of Institute for Employment Research (IER) at the University of Warwick. In this blog, he discusses the popularisation of the belief amongst policymakers, that robots are coming to take our jobs.

Popularised by Frey and Osborne’s 2013 report The Future of Employment: How susceptible are jobs to computerisation, there is a belief amongst policymakers that the robots are coming to take our jobs. It the report, Frey and Osborne claimed that 47% of existing jobs will disappear – and soon. Given that they are based at Oxford, that claim seemed credible to many policymakers. A raft of reports soon followed making similar claims but with different numbers and also signalling the potential vulnerability of even highly skilled jobs.

Some countries, such as Germany, have actively embraced this development as part of Industry 4.0 or the 4th industrial revolution. Centred on its manufacturing sector, Germany promotes a mixture of artificial intelligence (AI) and advanced robotic automation. With this new digital technology, clever robots undertake both manual and mental tasks. Sensibly, Germany complements Industry 4.0 with Work 4.0 and policy intended to futureproof the employability of its workforce and avoid the social disruption that mass job losses would bring.

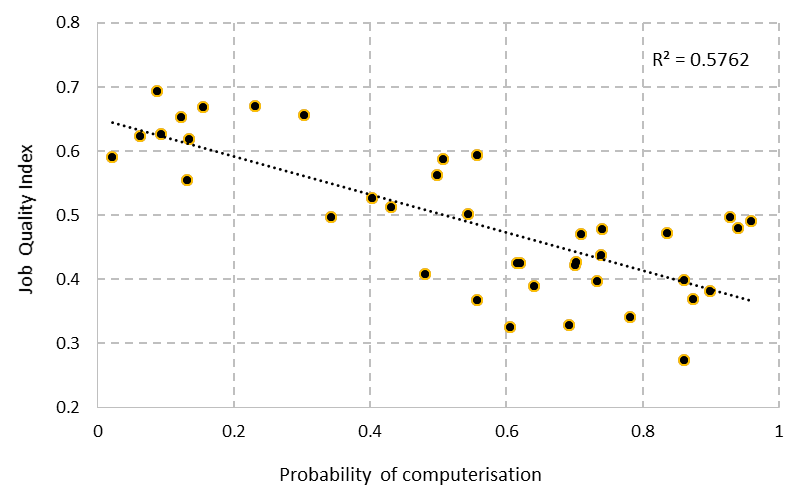

Elsewhere, more nuanced commentary claims that high-skilled workers will be relatively safe. Using Frey and Osborne’s methodology, IER collaborator Rafa Muñoz-de-Bustillo and his colleagues analysed 39 occupations across Europe and their probability of being replaced by the clever robots. Simplifying their findings, the top left cluster in the scatter graph below shows those occupations with higher skill and less probability of being replaced; those occupations towards the bottom right are lower skill and have higher probability of being replaced.

However similar arguments surfaced in the 1970s when a 3rd industrial revolution driven by the introduction of micro-chips was being heralded. And, parking discussion of what constitutes STEM occupations (a task being undertaken currently by my IER colleague Peter Elias for the Royal Society), STEM occupations have been singled out as the major beneficiaries of such revolutions.

For example, in 1979, Clive Jenkins, the leader of what might now be called the union for STEM workers, the Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs, published The Collapse of Work. In it, he and his co-author Barrie Sherman argued that by the mid-1980s micro-chips would wipe out most jobs, leaving only software and technical workers to operate highlight automated companies. Academics in universities and polytechnics would be needed to train these STEM workers and, for the enlightenment and entertainment of those without work, poets and clowns respectively (and I exaggerate only slightly). However this collapse of work would be welcomed, they claimed, because most jobs were awful, just plain drudgery. ‘It is an occasion for hope, not despair,’ they said. The mass of the population, with their new non-working lives, would be supported by a welfare system paid for by the raised profits of the more efficient, more productive automated companies, they asserted.

It didn’t happen. The problem is that most claims about the impact of new technology – digital or otherwise – are based on forecasts based on economistic modelling or are simply predictions. Little empirical data exists. A soon-to-be-published new survey of UK senior managers conducted for the CIPD by my team at IER attempts to fill this gap. Its findings reveal a more mixed set of job outcomes in companies that have already invested in digital technology. Initial findings indicate that it is high-skilled workers STEM workers (e.g. professional and higher technical staff) who are most likely to be most affected by the introduction of AI.

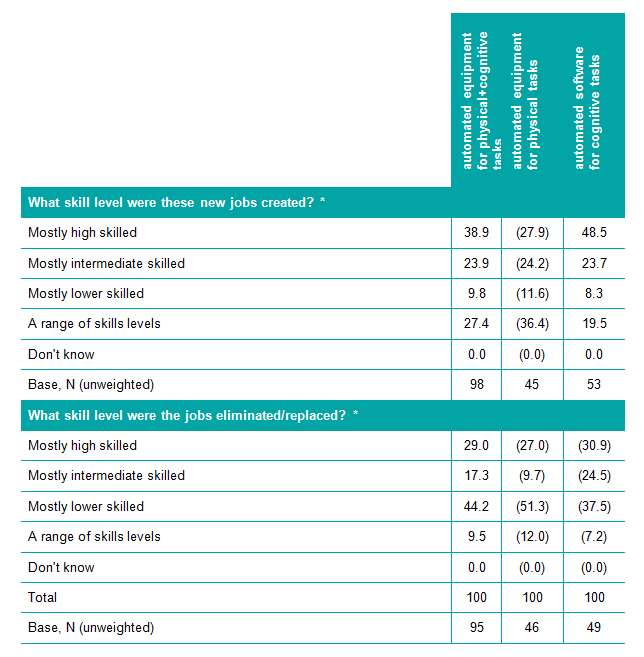

Generally, two-fifths of the organisations reported job losses with the introduction of some form of AI. Around a half reported no job losses and another two-fifths reported jobs being created. What is significant, however, is that the jobs created following the introduction of automated equipment using AI for physical (manual) tasks tended to be across a range of skill levels, the jobs created as a consequence of software using AI for cognitive (mental) tasks were more likely to be highly skilled, as the table below shows.

Beyond the sophisticated economistic modelling and bold predictions, it seems that outcomes in real organisations introducing clever robots is more mixed. There is both job loss and job creation. Moreover whilst there is significant churn in jobs for high-skilled STEM workers, they are benefiting overall from the introduction of AI. The future therefore looks less bleak, particularly for high-skilled STEM workers.