In recent weeks I have spoken to colleagues from across the sector and while there is no doubt that there is a great deal to be proud of in terms of the emergency response, there are some complex and wicked questions we will need to work on together to answer. My conversations with member institutions and stakeholders from across the sector have confirmed that one of the big questions for higher education institutions is when we open our campuses, HOW are we going to do that? The forces for doing so are great, the uncertainties around how to do so are extraordinary, and the risks involved are profound. For this reason, I am delighted that Advance HE is this week launching a rapid, generative project to collaboratively explore with the sector Creating Socially Distanced Campuses and Education. The project will be open to representatives from Advance HE member institutions from across the globe and I am sure that the outputs will assist participants to develop successful, socially distanced on campus education in their specific context.

Alison Johns

CEO, Advance HE

THE STORY SO FAR

Wikipedia (i) usefully defines social distancing as “a set of non-pharmaceutical interventions or measures taken to prevent the spread of a contagious disease by maintaining a physical distance between people and reducing the number of times people come into close contact with each other”. Historical accounts, including the Bible, show that social-distancing measures date back to at least the fifth century BC, responding to everything from the plague, leprosy and polio, to more recent severe strains of influenza and the SARS outbreak in 2003. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC (ii)) in the United States informs people that “social distancing, also called ‘physical distancing’, means keeping space between yourself and other people outside of your home. To practice social or physical distancing:

- Stay at least 6 feet (about 2 arms’ length) from other people,

- Do not gather in groups,

- Stay out of crowded places and avoid mass gatherings.”

In response to COVID-19 we have seen social distancing measures on a scale never experienced before, implemented with variations in approach by governments all around the world to protect their populations by reducing infection rates and ‘flattening the curve’ as regards the severity of the epidemic’s peak. The consequences of not introducing social distancing are stark. Focusing on the UK, infectious disease mathematical modellers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine forecast “that an unmitigated [no social distancing] epidemic could result in 16-30 million symptomatic COVID-19 cases and 250,000-470,000 deaths” and “in this scenario the UK’s NHS’s [National Health Service] hospital and ICU bed capacity would be massively exceeded”(iii).

Alongside this, periods of ‘lockdown’ have been introduced to isolate households and prevent travel and circulation for all but essential workers. The closure of business premises and public buildings has been key to enforcing social distancing, despite the economic consequences, and universities, schools and colleges have all been part of this.

In China university campuses did not re-open to students following the Chinese New Year (25 January 2020) public holidays and other stringent access controls were introduced. With the rapid spread of COVID-19, it was not long before other university systems around the world followed suit, with a shift away from classroom teaching and voluntary campus closures. Accompanying this there has been the most extraordinary pivoting of educational provision. To continue teaching and to support students an unprecedently rapid move to on-line teaching and assessment has occurred, involving prodigious efforts and incredible ingenuity from the whole higher education community.

What a story so far! But in many ways, this is just the beginning. What happens next will determine so much, from the educational and life prospects of a generation of students to, potentially, the sustainability and survival of some institutions. Where will we be when the shadow passes?

POSSIBILITIES AND UNCERTAINTIES

For eight years I had the extraordinary privilege of working at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) as Head of Staff and Educational Development. The School counts Chris Whitty, Chief Medical Officer for England and Honorary Professor of Public and International Health, amongst its alumni, and is known around the world for its outstanding academic and clinical expertise in public and global health, infectious disease research, epidemiology and many other related disciplines. In relation to the coronavirus pandemic, LSHTM is involved in many different aspects of COVID-19 research as well as providing guidance to those responding around the globe. Working at the School, observing teaching and supporting staff, one inescapable impression you come away with is the intricacy and challenge of predicting future events.

On a daily basis we hear from scientists and medical practitioners, quite rightly, how it is too early to draw conclusions and how it would be dangerous to make certain forecasts and predictions. A huge international effort is going into clinical research, disease modelling, data processing and public health advice, with universities often at the forefront, and the trialling of vaccines, treatments and other interventions is moving ahead at an unprecedented rate, but at this stage it is all about possibilities and uncertainties:

“It’s always important to be very honest about what we know and what we don’t. There are quite a lot of really critical questions we don’t know the answer to now.”

(Professor Chris Whitty, UK Government Public Briefing, 10 Downing Street, 19 March 2020.)

Just like every other sector of society, higher education institutions face the dilemma of trying to fathom what happens next. There is a series of questions that all sectors face:

- When and how will lockdown end?

- What kind of continuing health protection and social distancing measures will there be?

- What if there is a second (or third) spike in COVID-19 cases?

- Will there be further phases of lockdown?

- What if there are regional variations or age variations in how social distancing operates?

- How nervous will people be about socially interacting?

- What will national and international travel provision look like?

- What if vaccines or effective treatments come along earlier/later than expected?

- Other…?

Within the higher education sector itself there are a combination of ‘Will we?’ and ‘How to?’ questions starting to boil away with regard to students and learning and teaching, mainly focused on the start of the next semester, but with a range of other key dates in mind for providers with multiple start-dates and other educational formats and structures.

Will we…?

- Will we receive any/many new international students?

- Will we see current international students returning?

- Will we meet our targets as regards domestic students?

- Will we continue to teach on-line for the start of the semester?

- Will we go for a blended format to reduce student numbers on campus?

- Will we teach some students/courses on campus and teach others remotely?

- Will we defer/stagger some start dates?

- Will we collaborate with other universities to teach core modules on-line to larger cohorts?

- Will we be able to create classrooms and learning spaces that ensure social distancing?

- Will we meet student expectations?

- Other…?

How to…?

- How to inform students of what to expect (and when)?

- How to engage and re-engage students?

- How to induct and socialise new students, foster positive cohort identities and support transitions?

- How to enable the kind of differentiated and tailored approach that various types of courses and disciplines require (with access to any essential equipment and resources)?

- How to ensure quality, creativity and good practice in on-line teaching and assessment?

- How to continue to ensure access, inclusion and support for students with diverse needs and those from vulnerable groups?

- How to reduce disruption and dissatisfaction and ensure good student retention levels?

- How to manage and organise the campus estate for social distancing, high hygiene levels and also to provide enhanced levels of care and support (including for trauma affected students and staff)?

- How to provide a multi-faceted and holistic student experience (being at university)?

- How to assess staff capabilities, identify needs and support staff development?

- How to revise policy frameworks and codes of practice?

- How to proactively support the health and wellbeing of students and staff?

- How to nurture the academic community and the organisational culture?

- How to lead with compassion and kindness at the same time as responding with speed, focus and agility?

- How to come up with a sustainable financial model for the short-term (at least)?

- How to manage public perceptions?

- Other…?

It is far too early to call it a ‘new normal’. As the points above illustrate, there are many uncertainties to be overcome, challenges to be faced and experiences to be explored before anything starts to feel like normality. In response to COVID-19 necessity has been the mother of invention, and there will be some innovations and new practices that institutions will want to continue to embrace, but there are likewise many established aspects of university life and operations that we will wish to cherish and restore. There are many reports, for example, of academic staff feeling like Zoombies and yearning to get back into the classroom with students. Within all of this, individual institutional mission, purpose and distinctiveness should play its part in strategic choices over the longer term.

COLLECTIVE LEARNING

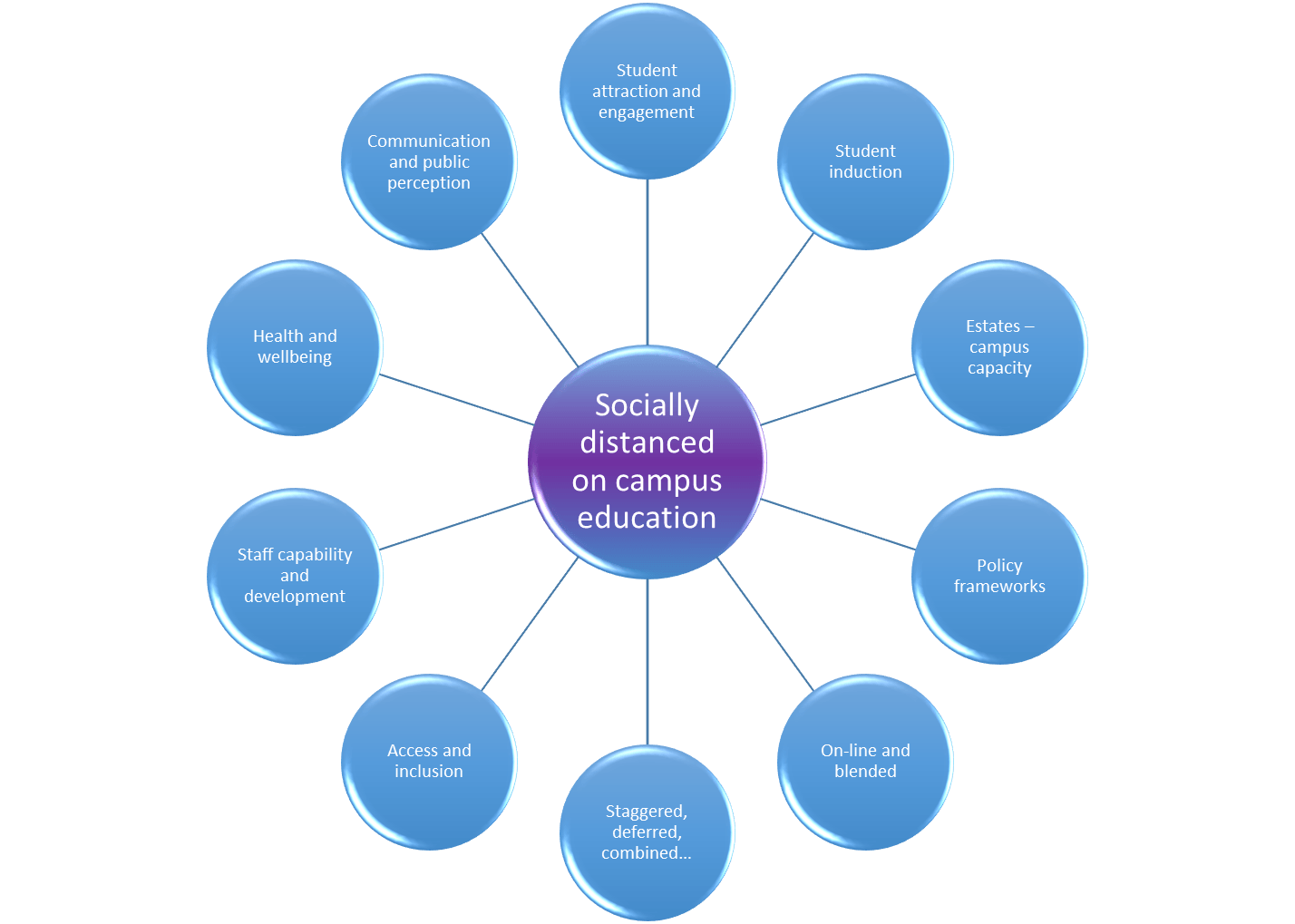

At this critical and precarious stage in the coronavirus response journey, there has never been a greater need for collective learning, sharing and planning. This piece began with the next big question for higher education, how and when are we going to re-open our campuses? As the previous section started to highlight, around that central question of achieving socially distanced on campus education orbit a number of key areas for close consideration:

To facilitate collective learning for the member institutions across the globe, Advance HE is this week launching a rapid, generative project to collaboratively explore these questions. This will be an international project driven at pace to match the swiftly unfolding situation that surrounds higher education. Targeted at senior colleagues with responsibility for planning, leading and managing educational programmes, its purpose will be threefold:

- To enable high quality conversations,

- To share information, inspiration and intelligence,

- To co-create solutions to specific aspects of the challenge.

Full details of the project will be shared with Advance HE member institutions later this week, but in outline the Creating Socially Distanced Campuses and Education project will involve:

- A dedicated Advance HE Connect Group for on-line information sharing and exchange,

- Over the next three to four weeks, a series of international workshops facilitated on-line for conversation, challenge and co-creation,

- Based on the above, a series of short leadership intelligence reports to support planning and decision making within institutions.

Moving forward, the struggle of achieving balance lies at the heart of policy making in all aspects of the coronavirus response: public health and economic health; keeping people safe and keeping people engaged; physical health and mental health; policy values and social values; the list goes on. And balance will be key to university decision making over the coming weeks and months, particularly balancing the needs of students with the needs and responsibilities of the institution and the needs of society.

Doug Parkin, 03-05-2020

Doug Parkin is Principal Adviser for Leadership and Management at Advance HE and was previously Head of Staff and Educational Development at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

i. Wikipedia page on Social Distancing - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_distancing (accessed May 2020).

ii. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) webpage on Social Distancing, Quarantine, and Isolation:

Keep Your Distance to Slow the Spread - https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/social-distancing.html (accessed May 2020).

iii. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine webpage - Estimates for the relative impact of different COVID-19 control measures in the UK (3rd April 2020) - https://www.lshtm.ac.uk/newsevents/news/2020/estimates-relative-impact-different-covid-19-control-measures-uk (accessed May 2020).