Well, the future isn’t what it used to be… (a saying attributed to an IBM executive concerning future trends in personal computing around 1992). And that poses a problem for strategic planning. In just about every sector and in a very short time the crisis brought about by COVID-19 has gone further than creating critical levels of uncertainty, it threatens to smash and tear apart some of the social and economic paradigms that are the unspoken foundations of most strategies. The givens are gone, if one can put it that way.

“Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future”Niels Bohr, 1922 Nobel Laureate in Physics

This clever quote encapsulates why strategic thinking and planning is a challenging activity at the best of times – those ‘best of times’ being when there is reasonably high confidence about the future through a range of mostly positive signals. Even if an organisation is in the difficult position of facing a set of negative strategic signals, reasonable levels of confidence regarding the developments or trends concerned are at the very least a basis for forecasting and resultant planning decisions. However, if key paradigms dramatically shift, such as how society fundamentally interacts or normal expectations regarding worldwide international travel, then the future becomes an undiscovered country. And this is extremely problematic as the future is where we are going to spend the rest of our lives.

Strategic Inversion

The current crisis has given rise to what might be termed ‘strategic inversion’. Part of strategic thinking involves identifying a set of appropriate time horizons to work with. These might, for example be one year, three years and five years. More ambitiously, it could be three, five and ten years, but even before COVID-19 it had become generally recognised that strategic planning horizons were drawing closer as cycles of change, development and innovation, particularly technological, grow ever more fast-paced. Selecting a near, mid and far horizon for strategic thinking is normally (I emphasise ‘normally’) a key first step, and each requires a different approach:

- Near horizon – the difficulty here may be that many of the drivers and requirements are already locked in place and visible, in many instances based on pre-existing commitments and ways of working, resulting in a limited spectrum of choice for decision making, and so leaders may end up with a largely operational focus, although there may still be some sense-making involved. The approach here will tend to be pragmatic.

- Mid horizon – this is often the sweet-spot for strategic thinking. Like a good golf swing, you neither catch the ball too early nor too late. In strategic terms there is the optimal balance between those factors that are known and can be controlled or influenced and those which are critically uncertain and require business insight, informed conjecture and imagination to consider. This is where scenario planning (scenario analysis) can be a particularly powerful tool, looking to imagine a range of alternative futures based on forecast variables. The approach here will tend to be predictive.

- Far horizon – here the experience may feel like future gazing. An important process, and more than an indulgence, it can be highly stimulating to think creatively and collectively regarding what may emerge from the hazier and more distant horizon. Linked to the mission and purpose of the organisation, how could the world be different in five- or ten-years’ time? This can be a great source of inspiration, but some leaders may hesitate to value all of the intelligence coming from these reflections as at such a distance it can be very difficult to discern patterns and separate out the strategic signals from other background noise. The approach here will tend to be speculative (hopefully enlightened speculation).

What is currently being experienced is an inversion of the above; the near strategic horizon has gone dramatically out of focus whilst the mid and far horizons offer the hope of greater stability. There is a profound perturbation in the system. Suddenly the near horizon has become highly volatile and speculative and senior leaders may feel a greater sense of certainty regarding the state of the world in two- or three-years’ time when ‘normality’ resumes (perhaps…).Best- and worst-case scenarios abound, in the press, on social media and in the private on-line conversations of institutional leaders. Having fought through the exigencies of the immediate COVID-19 crisis response, the next set of questions and possible actions hang ominously in the air. And business plans, those documents that capture and aim to operationalise the near horizon with clearly resourced goals and intentions, look at best in need of revision and in some cases lamentably unachievable.

As part of this inversion in strategic thinking there is an urgent need to bring some of that predictive, mid-horizon approach described above to short-range planning. Exploring scenarios in a creative way for horizons as close as three, six and twelve months may currently be the best use of strategic energy as the hard-to-forecast consequences and unpredictable impacts of the COVID-19 crisis ripple away.

Focus and Choice

As a definition of strategy, the idea of shaping the future is a good place to start. The origins of the term suggest ‘the art of a general’ from the French stratégie or a multitude/army or ‘across a wide plain’ from the Greek stratos. A fuller definition of what it means to ‘be strategic’ used on some Advance HE development programmes is as follows:

Driven by a purpose, and conscious of the environment, shaping the future to take advantage of our strengths, capabilities and distinctiveness.

An emphasis on purpose at the start of this definition brings strategy back to a core appreciation of why the organisation exists and linked to this, at the end of the definition, its cherished sense of distinctiveness. Writing about a purpose-driven approach, Bartlett and Ghoshal (1942) assert that “its definition and articulation must be top management’s first responsibility”. This is the ‘why’ of the organisation, and without it the danger is that organisations start to serve themselves.

As part of an Advance HE workshop-session called ‘Higher Education in Context’ participants are invited to work in small groups to discuss and complete together the sentence “The purpose of a university is…”. The responses and ensuing discussions are fascinating, bringing to light the complexity and depth of the role of higher education institutions, with answers ranging from the pragmatic to the philosophical. Wonderful, thoughtful reflections that illustrate the commitment and engagement of colleagues. On no occasion, however, has any group finished the sentence with the words “…to grow, make money and employ people”.

Purpose also provides the foundation of choice, in whatever circumstances the organisation finds itself, and fundamentally enables the basis for doing the right things for the right reasons. Focus and choice are ultimately the two key elements that make a decision strategic. Without them decisions are either reactive or, worse still, diffuse attempts to do everything to please everybody:

Strategy involves focus and, therefore, choice. And choice means setting aside some goals in favour of others. When this hard work is not done, weak amorphous strategy is the result.Richard Rumelt, 2012

Ensuring a robust business model that secures the financial sustainability of the organisation may be a central feature of any strategic conversation, but it is critical to remember that it is not an end in itself. It is the important but ordinary means to an important and extraordinary end, achieving the ongoing purpose of the organisation made sharp and relevant for the current context. A danger, then, in a crisis situation is that survival displaces purpose, and this can lead to decisions and actions that might have any number of unintended consequences, from diverting energy and resources into the wrong activities through to damaging public perceptions. The good use of scenario planning is really the reverse of this – using purpose to ensure survival.

Scenario Planning

Max McKeown puts forward the suggestion that “strategy is not really a solo sport” (2012). For people to ‘buy-in’ to a strategy and help make it, or at least some part of it, a reality they need to have a voice in its creation. A study carried out by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) in 2000 identified a series of strategic planning traps found in university contexts which included:

- Prepared in isolation,

- Prepared by one individual or a small group,

- Prepared without consultation.

Remarkably it is not unusual to find situations where ‘management’ consider there has been extensive consultation whilst the majority of ‘staff’ feel the new strategy has come out of nowhere. There are many reasons for such divergent perceptions, but part of the issue may lie in the degree to which engagement was active. Scenario planning (or analysis), involving well-chosen representatives from all parts of the organisation, possibly cascaded across organisational areas and levels, can be one way of creating a more authentic sense of collaborative engagement at the same time as drawing upon the creative energies of a diverse range of colleagues.

Scenario planning or analysis is “the most effective tool for dealing with uncertainty” (Grundy and Brown, 2002) when it comes to strategic thinking and planning. When faced with a fundamental discontinuity, “a major break between past and future” (ibid.) such as that brought about by COVID-19, the use of scenarios is an extraordinarily helpful way of creatively and collectively exploring transitional events.

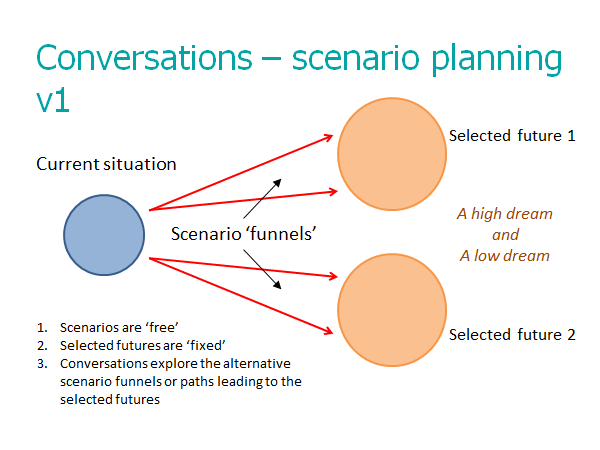

Without going into the details of facilitating scenario planning exercises, the process can be defined as “a means of assessing strategy against a number of structurally quite different, but equally plausible, future models of the world” (Van den Berg and Pietersma, 2016). There are two key approaches both of which can work well in different ways. Put simply one approach is to work backwards from a particular scenario (v1), and the other is to work forwards to see what alternative futures might arise (v2). The first (v1) involves selecting futures that are ‘fixed’, for the purposes of the exercise, and then the creative strategic conversations explore the alternative scenario funnels or paths that might lead to the selected futures:

For free and expansive thinking, it is important that the selected futures include a ‘high dream’ and a ‘low dream’. Particularly during times of adversity or crisis, or when strategic planning horizons have suddenly drawn close (strategic inversion) and there is a strong sense of urgency, it is important to deliberately keep the ‘high dreams’ alive with a close eye on purpose.

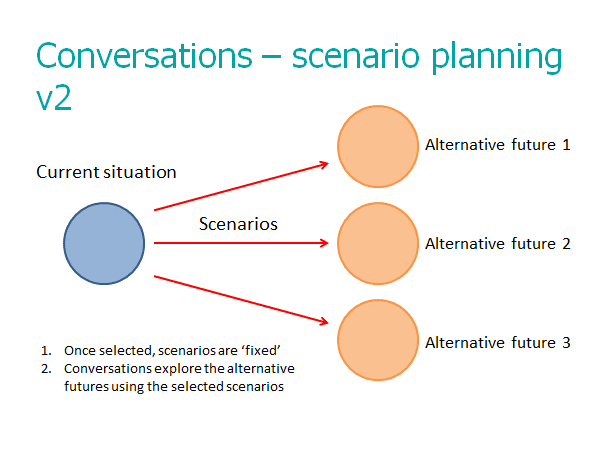

The second approach (v2) makes the scenarios fixed and then the creative conversations explore the possible alternative futures that might arise. This could involve either distinctly different scenarios or closely aligned scenarios with small but important variations, depending on what is useful for the organisation, the context and the challenges faced:

An important next stage in a scenario planning process is to list the likely impacts for the organisation arising from either the scenario journey (v1) or the alternative future (v2). These can then be categorised in relation to firstly the strength/severity of the impact and secondly the level of certainty that it might arise. Termed scenario impact analysis, a particular focus of strategic thinking should be directed to the areas of ‘critical uncertainty’ where the impact would be high but the likelihood of the situation arising (along with what might cause it to arise) is far from clear. It is in these areas that well-judged strategic decisions will make the biggest difference to the success of the organisation, along with the ability and the agility to constantly reassess. In the current context a key area of critical uncertainty that most higher education institutions face is with regard to student numbers, particularly international student numbers.

The Human Dimension

In many ways in educational establishments the human dimension is the only dimension that matters. The very definition of a university is community, and in that sense the purpose of a university is, or should be, a collective community endeavour. Regarding the current pandemic crisis as a type of creative destruction (Schumpeter, 1942) out of which a ‘new normal’ will emerge could be a dangerously utilitarian way of thinking. In no way do the ‘ends justify the means’ as tens of thousands die around the world. And yet forced innovation and an accelerated reassessment of both what is possible and what is desirable could lead to valuable enhancements in the longer term, and strategic leaders would be negligent not to be alive to such possibilities. However, the values that underpin such judgments need to be clear, putting people first, not technology, and having absolute clarity regarding the link between learning, discovery and human relationship.

Perhaps the greatest criticism that could be made of a strategy, certainly for a people-focused organisation, is that ‘there’s no heart in what you’re doing’. A strategy that speaks purely to actions and not values, that is reactive to circumstances rather than driven by purpose, and which cares for tasks and goals ahead of people and place, is not the way to shape the future, even when strategy development is driven by a critical sense of urgency.

The most strategic of strategic questions is purpose, linked to the identity of the organisation, and out of this steadfastly doing the right things for the right reasons.

Doug Parkin is Principal Adviser for Leadership and Management at Advance HE and was previously Head of Staff and Educational Development at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

All of our Covid-19 response resources can be found on our dedicated support page.

References

Bartlett, C. A. and Ghoshal, S. (1994) Beyond Strategy to Purpose. Harvard Business Review, November – December.

Rumelt, R. (2012) Good Strategy/Bad Strategy: The Difference and Why It Matters. London: Profile Books Ltd.

McKeown, M. (2012) The Strategy Book. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

HEFCE (Higher Education Funding Council for England) (2000) Strategic Planning in Higher Education, 24, Bristol.

Grundy, T. and Brown, L. (2002) Be Your Own Strategy Consultant: Demystifying Strategic Thinking – The Cunning Plan. London: Thomson Learning.

Van den Berg, G. and Pietersma, P. (2016) Key Management Models; The 75+ models every manager needs to know, 3rd edn. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1942) Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Abingdon: Routledge Classics (2010).