The start of the new semester is challenging, exciting, stressful and full of hope and anticipation for both students and staff. As staff, we all want our students to do well. We want students to fulfil their potential and achieve their hopes and dreams.

What are those hopes and dreams? For some, it is surviving the first year of their course! For others, getting across a borderline degree classification average. For others, the focus of the year is on securing an internship or placement. For some final year students, it’s getting 'the coveted graduate job.’

For those of us who love education and teaching (importantly, this is the vast majority of us working as academics in higher education), we can, and do, debate the merits of a liberal education system in which students do a degree for lots of reasons, underpinned by the ‘love of learning.’ However, the reality is that increasingly, and it is certainly the case in accounting and finance (my subject discipline), that students choose the course and choose to do it at my institution to enhance their future job prospects. It is my belief that university transforms lives and provides opportunities to students that they would not otherwise have had – and this includes access and opportunity to the graduate labour market (whatever that means these days).

Research (see Bullock et al. 2009; Gomez, Lush, and Clements, 2004; and Mansfield 2011), suggests that placement students have higher academic achievement in terms of final grades but they also report a greater increase in grades between Year 2 and the final year of the course in comparison to non-placement students. Research (see Mason, Williams, and Cranmer 2009) also shows that if a student does an internship or placement, they are more likely to get a graduate job.

In their study of differences in employment outcomes, HEFCE found that sandwich placements were associated with a significantly higher probability of progressing to further study or employment and of those in employment, a significantly higher probability of gaining graduate level professional occupations. The University of Bath found that Accounting & Finance students who undertook a placement year significantly increased their chances of attaining a 1st or 2:1 compared with their counterparts who took the same course without the placement year. There was a reported 13% attainment gap between Black and White students graduating in 2017-18. The ECU and HEA commissioned a report in 2008 to provide understandings and perceptions of degree attainment variation across institutions and among academics and students. This report provides no evidence of clear causal factors to explain degree attainment variation by gender or ethnicity. Since the report there have been many institutional case studies that highlight the complexity of the issue.

However, rather than just evidencing the gap, we need to assess and understand why Black students are marginalised and impacted in this way. This for me, has become the focus of my PedR Employability research.

I am a professionally qualified accountant who worked as a workplace mentor to graduates, prior to entering the academy. My first love is teaching but l also love researching teaching practices and analysing students’ experiences. The work that I undertake seeks to improve teaching, learning, assessment and future opportunities of students. So as it turns out, I have long been interested in pedagogy (PedR of teaching and employability) and scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL).

I recently moved from a very (frustratingly) under-rated post-1992 university, to a highly ranked, leading Russell Group university in the 2018/19 academic year. I had never been educated at a private/public school. Before doing my PhD, I had never studied at a Russell/Red-brick university and I did not train at one of the “Big 4” accounting firms. I quite frankly questioned whether I was good enough to be here. One year on, I have come to understand this 'imposter syndrome' is shared by marginalised students everywhere, regardless of whether they are at post-1992 or Russell Group universities.

The accounting and finance course that I teach on is highly selective (typically requiring AAA) and there is approximately 10% representation of Black students on the course. This is positive because it challenges the deficit model rhetoric that suggests Black students access higher education opportunities because of (wonderful) widening participation schemes. Many Black students are really, really bright and have high ambition and aspirations. However, a recent article by student magazine The Gryphon reported that Black students were awarded 1:1, at a rate that is four times less than White students in the academic year 2018-2019. In the last academic year, only 7.9% of Black students got a 1:1 degree compared to 33.3% of White students. This was an awarding gap of 25.4%.

Our hypothesis is that if we get more BAME students, particularly Black students (because they the lowest ethnic group achieving 'good degrees'), doing UK internships or placements, more BAME students (particularly Black students) will get a 'good degree' on graduation and enhanced access to the graduate labour market.

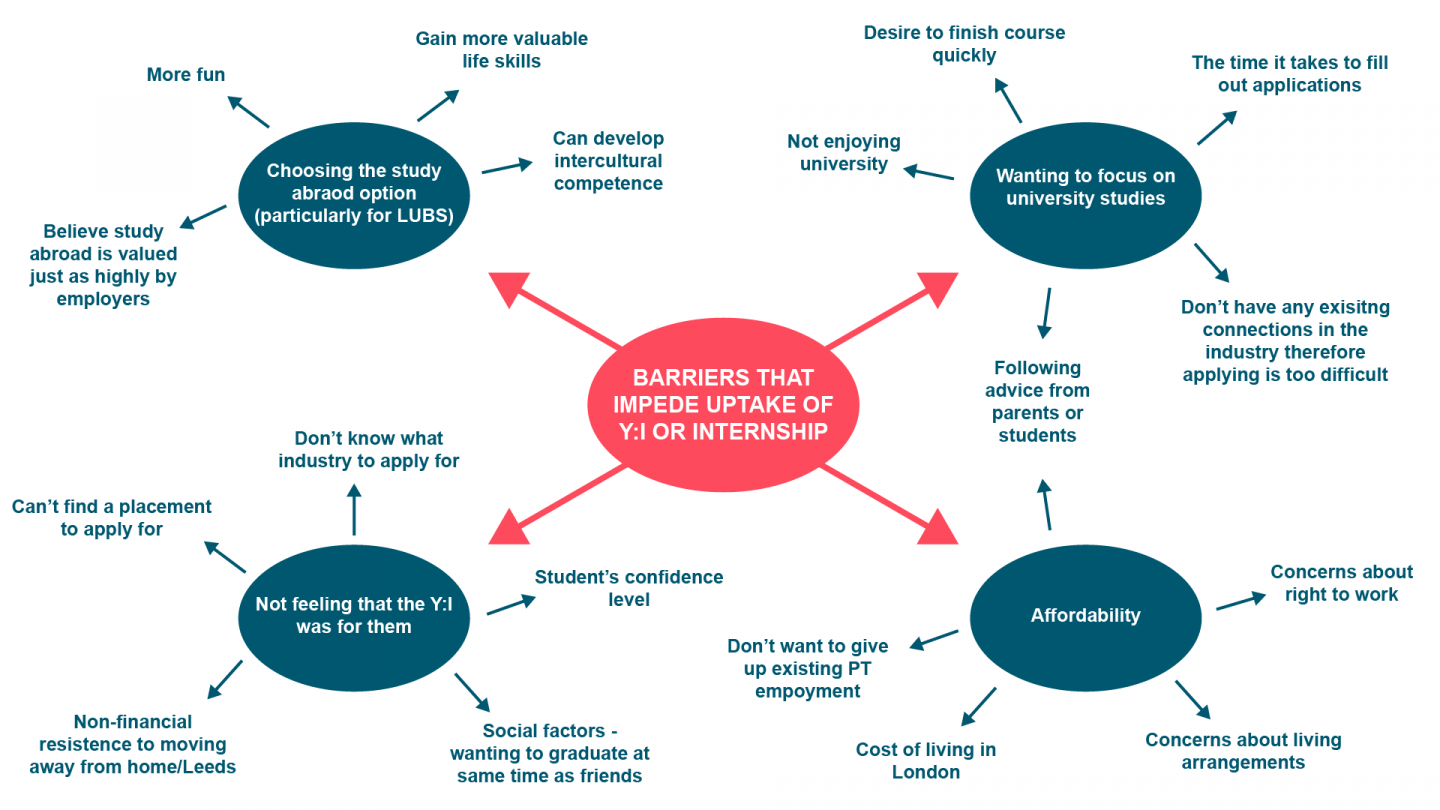

Will Southall, one of my undergraduate student researchers working with me on a PedR employability research project identified barriers to internships and placements from an extensive literature review. He used his literature review to devise a mind map (see Fig.1). The framing of themes from the literature review in this way, informed our approach to our focus groups conducted with students.

Figure.1 Barriers to industry and placements identified by students (reproduced here from a mind-map image by Will Southall)

Our initial discussions with BAME students has identified structural barriers, alternatives to internships/placements and personal trade-offs that are complex, inter-tangled and nuanced reasons contributing to why BAME students are not accessing UK internships/placements.

Analysis of the focus group data has led to some troubling initial conclusions that suggest these students need to engage in professional identity work. Employers exert a form of identity regulation when recruiting and selecting students into internships, placements and graduate jobs and some BAME students struggle to fit with identity regulation requirements of employers, for a wide range of reasons.

We explore the importance of identity, in relation to employability, further in our PedR employability case study.

Find out more about the ’Enhancing Graduate Employability: A Case Study Compendium’ here.