This blog is part of the Advance HE Thematic Series resource for ‘The intercultural curriculum’, this is an output of the Advance HE Scottish National Priority Plan.

The aim of the Thematic Series are to strengthen core academic capabilities of staff through the sharing of effective practice and focused theory, and to support institutional enhancement of Learning and Teaching, complementing and further building on their existing in-house work. Topics are identified by the Scottish Sector, and resources are authored and curated by colleagues from Scottish institutions, with case studies and blogs sourced from both national and international colleagues, and the resources aim to guide practitioners to relevant material and experiences to support them in developing their own teaching practice.

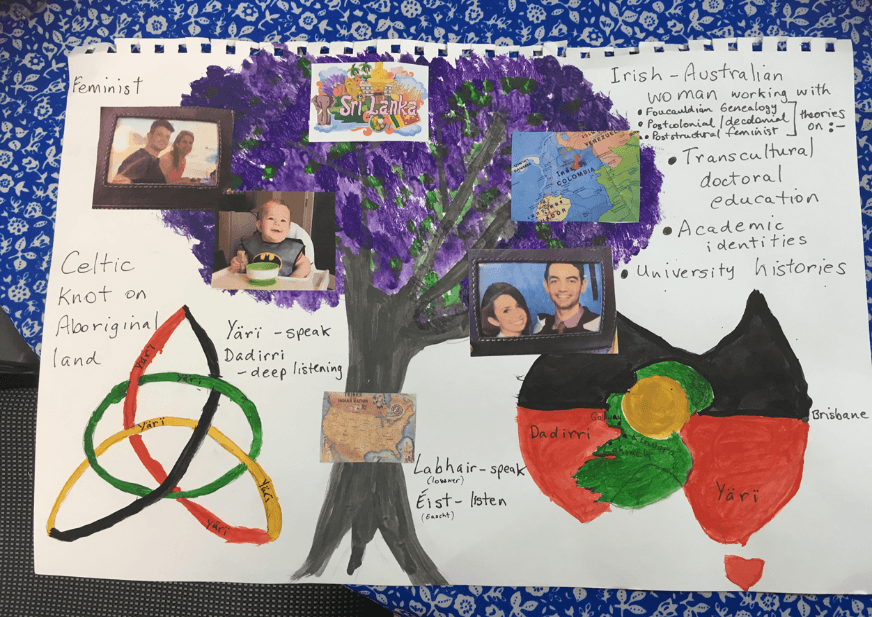

I’ve been thinking, writing and researching about the ‘intercultural curriculum’ for nearly 30 years. As an Irish-Australian growing up in Brisbane in the 1970s and 80s with a folk memory of colonisation and a sense of never quite fitting into Anglo-Australia, I became passionate about peoples’ histories, geographies and cultures. I continue to think long and hard about what it means to be of the formerly colonised people of Ireland and of those who colonised Australia. I call myself a settler/invader scholar and challenge myself every day about what this means for my work, for my research, for my desire to make a difference.

My first marriage was to a Sri Lankan Australian man, which is how I come to have Manathunga as a family name, and I am the proud mother of two intercultural sons. The intercultural character of my family has expanded in recent years as I have a Colombian daughter-in-law and an English-Australian daughter-in-law with Chippewa First Nations American Indian heritage. My little granddaughter is a complex mix of all of these rich cultural traditions. So, my reasons for a fascination with the intercultural have always been profoundly personal and, of course, as a committed feminist, political. I’ve always felt that the first step in any intercultural curriculum begins with interrogating our own cultural and political standpoints.

Most of my research has been on intercultural doctoral education and supervision. These years of thinking lead me to write a book called Intercultural postgraduate supervision: reimagining time, place and knowledge (Manathunga, 2014). This was a part theoretical and part empirical exploration of how history, geography and cultural knowledge played out the intercultural supervision of migrant, refugee and international doctoral candidates in Australia. Theoretically, I sought to rethink intercultural supervision through an array of postcolonial, feminist, Indigenous and cultural studies theories I loosely called ‘Southern’.

In the empirical part of my study, I uncovered evidence of transcultural and assimilationist pedagogies. What became clear to me was that assimilationist pedagogies operated with an absence of attention to time, place and diverse cultural knowledge. This approach to supervision seemed to be premised on a profoundly deficit view of cultural diversity and very low expectations of culturally diverse doctoral candidates.

By contrast, transcultural pedagogies placed time, place and cultural knowledge at the centre of supervision. What this meant was that supervisors were eager to know more about doctoral candidates’ prior intellectual, cultural and professional histories and knowledges and also gave students opportunities to develop all of the skills they would need to work as independent researchers into the future. In other words, they had a past-present-future approach to time in supervision.

These supervisors demonstrated a deep respect and curiosity about students’ geographies and cultures. They saw supervision as an open, relational and social place and were aware of the impact of personal issues on research and the dislocation students could experience as they grappled with new places, cultures and education systems. They stressed to students the importance of a healthy work/life balance and sought to incorporate students into a vibrant and inclusive research culture.

Transcultural supervision also operated as a deep commitment to valuing and learning more about diverse cultural knowledge systems. These supervisors were aware of the many different cultural ways knowledge can be constructed and were not expecting that their students would abandon or move away from their own forms of cultural knowledge. They recognised that Western or Northern knowledge and research practices were merely an additional set of theoretical and methodological resources that doctoral candidates sought to add to their repertoire.

Transcultural supervision also involved proactively building bridges for doctoral candidates into Western/Northern knowledge and research practices. These included the following practical strategies:

• Providing structured help with the literature review and other research tasks

• Providing oral and written feedback

• Encouraging students even when early drafts required a lot of work

• Encouraging students to use tape recorders in meetings

• Guiding and supporting writing for publication

• Providing career mentoring about what it means to be a researcher

• Helping students to develop their own voice (Manathunga, 2014).

You’ll notice the shift here from intercultural to transcultural. This began with a fascination with Mary Louise Pratt’s (2008, p. 6) postcolonial concept of ‘transculturation’ which described how ‘subordinated or marginal groups select and invent from materials transmitted to them by a dominant … culture’. In other words, transculturation in doctoral education involves the creation of new cultural possibilities and new ways of knowing and being for culturally diverse candidates and, sometimes, for their supervisors.

Over the last few years, there has been a general and semiotically important shift towards the term ‘transcultural’ in the literature on education and cultural diversity. Trans is a prefix meaning ‘across’, ‘beyond’ or ‘through’. In a recent article Niranjan Casinader and I explored understandings of culture.

Niranjan has argued that ‘culture consists of myriad patterns of thought that are given special significances within the context of a particular way of life’. He suggests that cultures generate ‘a reservoir of thinking, a mental well of all the attitudes and perceptions that people within that culture bring to bear on the activities that they undertake’ … (Casinader,2014, p. 43). He sees transculturalism as a post-globalisation progression from interculturalism, where identity is not necessarily circumscribed by ethnicity or location. Recognising the spatial dimensions of culture …, Catherine has argued that ‘culture is a place of thought’ (Manathunga,2013, p. 67) (Casinader and Manathunga, 2019, p. 6).

Moving to the term transcultural seeks to reflect a recognition that, for many people, including my own transcultural family, being across (trans) rather than between (inter) cultures is an everyday reality and creative force for thinking, knowing, doing and being otherwise.

Since publishing this book, I have embarked on new research journeys with my transcultural and Indigenous colleagues Qi Jing, Michael Singh and Tracey Bunda. We are Chinese, Punjabi-Australian, Irish-Australian and Ngugi/Wakka Wakka First Nations Aboriginal Australian scholars. We call ourselves the ‘Deadly Research Team’. ‘Deadly’ is an Aboriginal English term for ‘awesome’. Interestingly, this term is used in Irish English in a similar way. We seek to mobilise transcultural and First Nations’ (Indigenous) cultural and linguistic knowledge among migrant, refugee, international student and Indigenous doctoral candidates (Singh, Manathunga, Bunda and Qi, 2016). We have been using life history methodologies (Bunda, Qi, Manathunga and Singh, 2017) and arts-based visual methodologies (Manathunga, Qi, Bunda and Singh, 2019) to investigate how we might reimagine history in transcultural doctoral education. In particular, we have extended Zerubavel’s (2003) ideas about time maps to create a Southern methodology of time mapping that seeks to chart transcultural and Indigenous candidates and supervisors’ histories, geographies and cultural knowledges. This has allowed us to re-present our cultural and political standpoints visually. Here is the story I began this piece with represented as a time map:

On behalf of our Deadly Research Team, I invite you to think about how you might map your own histories, geographies and cultural knowledges and engage in transcultural pedagogies in your work.

References

Bunda, T.; Qi, J.; Manathunga, C. & Singh, M. (2017). Enhancing the Australian doctoral experience: Locating culture and identity at the centre. In A. Shahriar & G. Syed (eds.) Student identity and culture in higher education (pp. 143-159). London: IGI Global.

Casinader, N. (2014). Culture, transnational education and thinking: Case studies in global schooling. London: Routledge

Casinader, N. and Manathunga, C. (2019). Cultural hybridity and Australian children: speaking back to educational discourses about global citizenship. Discourse: studies in the cultural politics of Education. 42(2). DOI: 10.1080/01596306.2019.1593108

Manathunga, C. (2013). Culture as a place of thought. In T. Engels-Schwarzpaul & M. Peters (eds.) Of other thoughts: non-traditional approaches to the doctorate (pp. 67-82). Rotterdam: Sense publishers.

Manathunga, C. (2014). Intercultural Postgraduate Supervision: reimaging time, place and knowledge. London: Routledge.

Manathunga, C.; Qi, J.; Bunda, T. and Singh, M. (2019): Time mapping: charting transcultural and First Nations histories and geographies in doctoral education. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, DOI: 10.1080/01596306.2019.1603140

Pratt, M. (2008). Imperial eyes: Travel writing and transculturation (2nd edition). London and New York: Routledge.

Singh, M.; Manathunga, C.; Bunda, T. & Qi, J. (2016). Mobilising Indigenous and non-Western theoretic-linguistic knowledge in doctoral education. Knowledge Cultures,4:1, 56-70.

Zerubavel, E. (2003). Time maps: collective memory and the social shape of the past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.